The Resurgence of Louise Jopling

Sold for £13,800 at Wilson55

28th March 2025 | by Anna Lambert, Art Department Assistant on behalf of Wilson55

Louise Jopling was one of the most famous female artists of her day, achieving a level of popular and critical success that was unfortunately so rare for a woman during the 19th and early 20th centuries. She may not be a household name in the same way that her contemporaries (and friends) John Everett Millais and James McNeill Whistler are today, but her painting, “Saint Bride”, currently being offered in our upcoming Fine & Classic Sale is proof enough that this is due to no lack of talent on her part. Rather, Jopling has been victim to the unfair way in which art institutions and history have notoriously treated the female artist from this period. The arrival of her painting at our saleroom follows a well-deserved revival in interest over her life and career by these institutions, and will surely only contribute to the increase in attention that she is currently receiving after her past century of obscurity.

Lot 116 - Louise Jopling (British 1843-1933), "Saint Bride", signed, titled "Paul said, and Peter said, And all the saints alive and dead vowed she had the sweetest head, Bonnie sweet Saint Bride" and with the artist's address - '3 Logan Place, Kensington' and original price of £100 on artist's label verso, with Dicksee & Co., Liverpool label dated 1902 on verso, oil on canvas.

Sold: £13,800

Jopling was born in Moss Side, Manchester, in 1843, but was living in Paris with her husband and their two children when her husband’s employers’ wife, the Baroness de Rothschild, encouraged her to study art after being impressed by her pencil sketches. After an art education in Paris and London, Jopling was able to make a career for herself through painting, and the de Rothchild family remained good friends and patrons of hers, with several of their family portraits making up her known oeuvre. While she was a capable painter of a wide range of subjects, such as interiors, narratives and genre scenes, she mainly relied on painting portraits to earn a living, doing so well in this that she became the main earner in her family. After the end of her marriage with her first husband, and his death years later, Louise was able to remarry and did so to Joseph Middleton Jopling in 1874. It was through her new husband, and his own career as a watercolour painter, that she became close friends with his friends, Millais and Whistler. These kinds of associations worked to place her in the middle of artistic society at the time, and the portraits that these men painted of her only furthered her fame within it. In this second marriage, Louise was again the higher earner. She later made history as one of the first women to be elected to the Royal Society of British Artists in 1901, and she exhibited at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition often. Her painting, “Blue and White”, was exhibited at the 1896 Royal Academy Exhibition, where it was bought by William Hesketh Lever, and now makes up part of the Lady Lever Art Gallery’s collection in Port Sunlight.

Photograph of Louise Jopling, by Herbert Rose Barraud.

Joseph Jopling died in 1884, and Louise married for a third time, keeping the name Jopling for professional reasons. With this marriage came a new house in Kensington, and it was in this house that Jopling opened her own art school for women in 1887. Despite her successes, Jopling’s artistic career was still affected by her being a woman, a fact that she was highly aware of and expressed frustration over in her memoir, Twenty Years of My Life (published in 1925). Jopling lost out on a 150 guinea commission to her male contemporary Millais, who was paid 1,000 guineas for the same project, and while Jopling exhibited at the Royal Academy, women were unable to achieve full membership at the time, meaning that Jopling was constantly reliant on committees of men to select her work for exhibition. The study of human anatomy through life drawing classes was believed to be the cornerstone of traditional art education. It was also another activity that was made inaccessible to women as it was deemed inappropriate, the nude was a subject reserved for the male artist. Jopling was an outspoken advocate for women having access to the same art education and exhibiting rights as men, so famously made life drawing a feature of her new art school for women.

It is through this belief in equality between genders that one can connect Jopling’s lived experience with her painting of St. Brigid (also known as St. Bride). St. Brigid (c. 451 - c. 525) is venerated as one of Ireland’s three patron saints, noted for her love of nature, social justice, and equality. While the details of St. Brigid’s life shift between accounts, hers is ultimately the story of a woman founding a monastery in Kildare, built on her belief that there should be no distinction between how male and female followers of religion are treated or taught. This immediately brings Jopling’s own art school to mind, relating the two women through the way that both of their institutions were grounded in similar ideas of gender equality and education, despite the thousands of years that separate them. Jopling was also an active supporter of several women’s suffrage campaigns and organisations, offering further explanation for her attraction to the figure of St. Brigid. Understanding this, the painting that Jopling produced of St. Brigid was therefore just as radical in its day as it is beautiful.

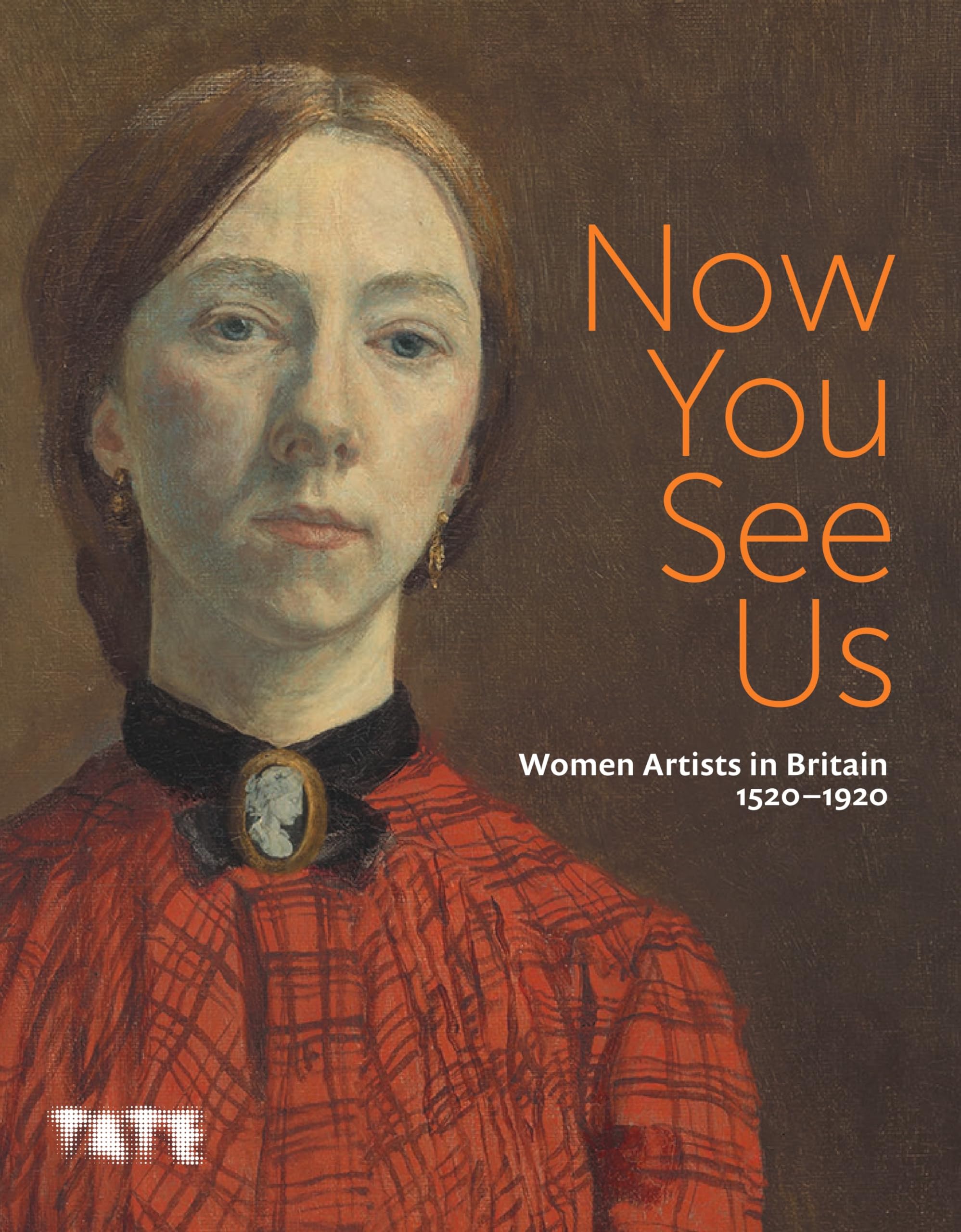

As previously mentioned, Jopling has fallen into some obscurity since her death in 1933, mainly due to the way that female artists have been dismissed by past art historians and curators. Female artists used to be judged by the extent to which their artworks were expressive of the qualities of a genteel woman, and as it has been noted, this was not what many of Jopling’s artworks set out to do. Understanding her painting “Saint Bride” within its historical context shows us that some of her work was rather a direct challenge to these societal expectations of women. Society is moving on though, and a revival in interest over forgotten female artists has worked to grant her some of the attention that she so arguably deserves. The Tate, for example, recently acquired her painting, “Through the Looking Glass”, which was then put on public display as part of their 2024 exhibition ‘Now You See Us – Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920', which aimed to spotlight and celebrate marginalised female artists. Efforts by other art historians have seen academic articles and books focusing on Jopling published in recent years and Professor Patricia de Monfort of the University of Glasgow is currently working on completing a full catalogue of Jopling’s works, making new information about Jopling, her circle and her interest in various social causes more accessible to wider audiences.

Tate, ‘Now You See Us, Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920’, Exhibition Guide Cover (2024).

Louise Jopling (British 1843-1933), “Through the Looking Glass”, oil.

Research into her catalogue by people like de Monfort have found record of over 750 works produced by Jopling, yet the location of the vast majority of these works remains unknown. The discovery of Louise Jopling’s “Saint Bride” at our saleroom presents buyers with the rare and exciting opportunity to own an increasingly important, and not to mention visually stunning, piece of art history.

Louise Jopling's “Saint Bride” sold for £13,800 during our April 2025 Fine & Classic Sale, after a fierce bidding war between several online and telephone bidders from the UK and abroad, setting her a new record at auction.

References:

Louise Jopling (1843-1933): A Research Project (Catalogue of Works) <https://www.louisejopling.arts.gla.ac.uk/>

The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, The 134th, 1902. (cat. no. 655) <https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/exhibition-catalogue/ra-sec-vol134-1902>

Donna Ferguson, ‘Tate Britain acquires first painting by pioneering English female artist overlooked for a century’, The Guardian, published 12th May 2024

Tate, ‘Now You See Us, Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920’ Exhibition Guide. <https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/women-artists-in-britain-1520-1920/exhibition-guide>

With special thanks to Professor Patricia de Monfort, University of Glasgow.